7 Questions With For All You Do Author Peter Mishler

Teachers need radical self-care and support in order to continue their life-changing work. That’s the premise behind Peter Mishler’s For All You Do, published by Andrews McMeel in May. In addition to being a writer of prolific poetry—including the publication of his collection Fludde, which won the Kathryn A. Morton Prize—Mishler has held a career as an English teacher for more than a decade. Mishler talked with Read Poetry about his most inspiring moments in the classroom, how poetry and teaching intersect, and more.

Kara Lewis (KL): What inspired you to write For All You Do?

Peter Mishler (PM): The mental and physical health of teachers is at stake. The job is very demanding, and continues to get more demanding. The positive side of this is that we have a better understanding of how to reach more students and how to understand where students are coming from. Therefore, there’s a lot of work to be done on behalf of our students.

At the same time, society is too dependent on teachers to shore up all of the needs our students have. It’s no surprise that teachers are leaving the profession. We can’t do this work well for the pay we currently receive. And we can’t do this work under the thumb of legislative bodies that don’t have teachers’ best interests in mind.

And yet, until we see the kind of action that would benefit both teachers and students and their families, we teachers are going to need to keep ourselves healthy to do the work we love. I decided to write For All You Do to help in that process of carrying on—to offer my experiences about how to do this work in sustainable ways that can be life-changing for both us and our students. The better we take care of ourselves as teachers, the more energy we have to push back against the institutional difficulties of education and get our needs met.

KL: In addition to your work as a teacher, you’re also an award-winning poet. How do these two roles intersect?

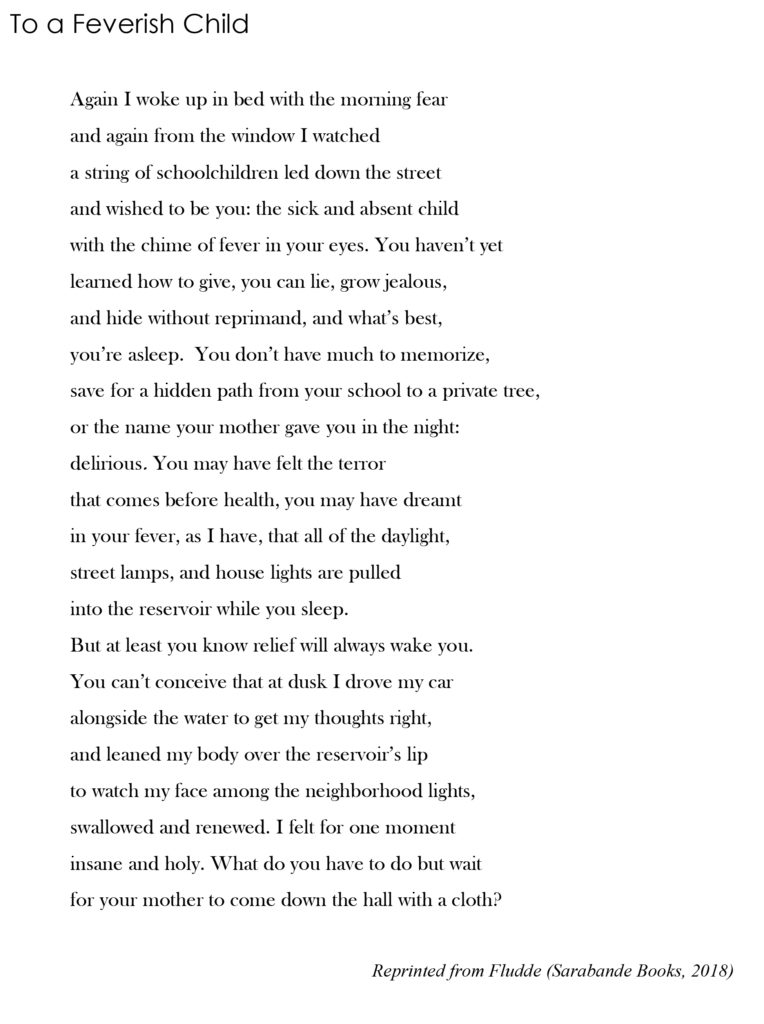

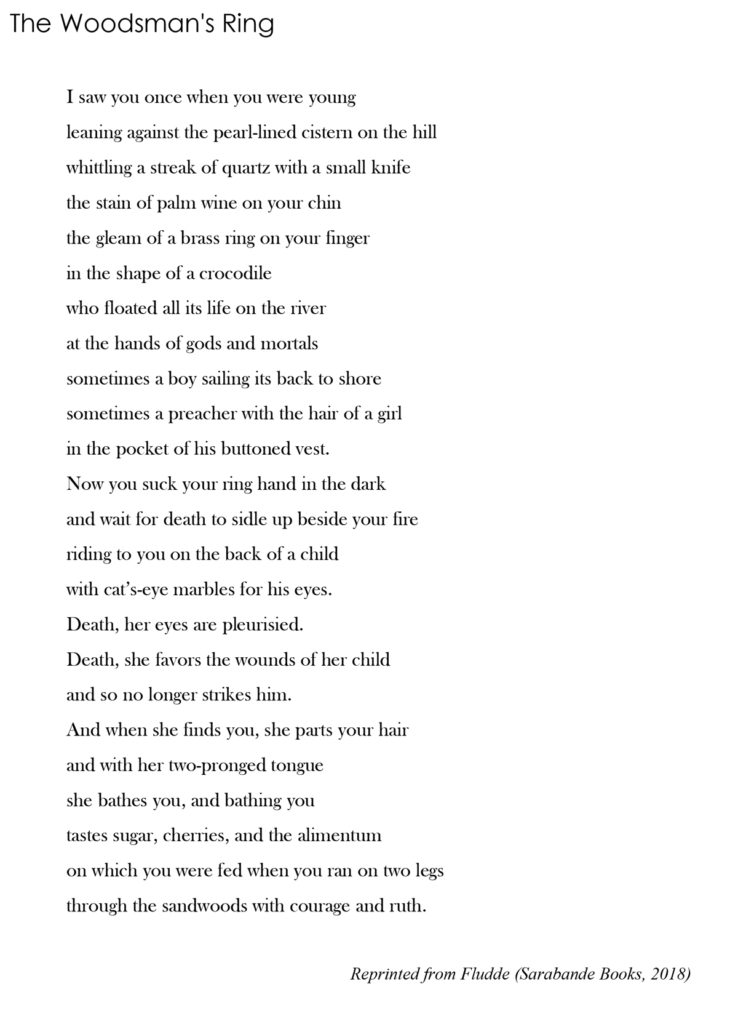

PM: Teaching is interacting intensely with a great number of other human beings on a day-to-day basis and colliding with the many forms of human emotion, as well as beliefs, identities, imaginations, thinking, and lived experiences of students and their families. Also embedded in all of this are the failures and successes of our neighborhoods, cities, states, and country. Since poetry is a process by which I use the tools of language to understand the most significant experiences of my life, I see my life as a teacher showing up in my poems.

KL: For All You Do pushes back against many misconceptions about teachers. What’s the biggest thing you wish you could tell non-teachers about teaching and education?

PM: I’d like people to know that our work with students is at the nexus of our society’s challenges and failures, as well as its progress. Those of us who do this work well are committed to providing care, relief, encouragement, love, structure, and support in the face of much of what ails our culture. We are enacting, in the way teachers can, ways of healing, as well as a vision for what we believe we can be.

I’d also add that there is a current talking point warning that teachers are engaged with “critical race theory propaganda” and are politically influencing children. I’d like folks with these opinions to know that teachers are dedicated to equipping all of our students with skills, knowledge, and experiences that we are certain will make their lives healthier, safer, happier, and more fulfilling. This does include having conversations about race and racism, as well as conversations about other forms of discrimination and inequity.

KL: What are your tips for teachers wanting to incorporate more poetry into the classroom?

PM: What seems to be effective is bringing poems into the classroom that are genuinely of interest to us as teachers because the writing is puzzling or beautiful or meaningful. Then, there can be real engagement with poetry because there is engagement with a teacher’s actual thinking and feeling. I often like to engage with poetry in my classroom by simply admiring its disposition, its sound, and the space it inhabits without trying to “do” anything with it. I also recommend purchasing full-length poetry collections and bringing these into class. Poetry collections demonstrate that the work of poetry is tangible, contemporary, and physical—a living thing. As a young person, I’m not sure I even knew that someone could write a whole book of poems, and I certainly had a limited view of who was writing poems. I thought they mostly existed on print-outs or in thick anthologies.

KL: How did the process of writing For All You Do, an inspirational book, differ from your usual process of writing poetry? Were there any unexpected similarities?

PM: Writing For All You Do was about being simple, honest, and even a little sentimental. But how could I help it, thinking about the students, mentors, friends, and the rich experiences I’ve had with them all? I felt a bit uncertain writing so openly because it was new for me, and I wanted to avoid sounding like I was selling wellness culture or adopting the preachy tone of the corporate trainer, which is what I thought writing about my professional life would have to look like. But what I found out was how moving the writing was for me, and how much I meant what I was saying. That felt like writing a poem—not being certain about what I would say, but ultimately feeling like something was communicated through me, something that felt authentic and right.

KL: Did you have any favorite educators who inspired you to pursue poetry? If so, how did those experiences stand out and how do they influence your own approach as a teacher?

PM: My Latin teacher in high school taught us English and Latin prosody—the metrical patterns of poetry—and it changed my life. I became fascinated by the fact that there was a way to articulate what poetry was doing at the rhythmic level, the same way as with music. This experience taught me that as a teacher I should never shy away from trying to teach difficult material. Students thrive in environments where they are seen for their capacity and capability. I’ve also had a handful of teachers who impacted me because they took our creative acts seriously. I had a teacher in high school who would let me read my poems to the class to begin the period. I had another who referred to me as a filmmaker and I’d be bursting with excitement to show my videos to the class. These acknowledgments meant the world to me because all I wanted was for someone to see me the way I saw myself. I’m very intentional to make sure I bring this spirit to my students.

KL: What’s next for you creatively, as both a poet and an educator?

PM: Next year I will be leading the English department for my public school district’s virtual school, which is a new endeavor for us. I hope to be able to learn more about how virtual learning can offer a much-needed alternative to in-person public school. I’m also currently finishing a second collection of poems, and am looking forward to sharing it. It’s dedicated to my son.

Order For All You Do here.