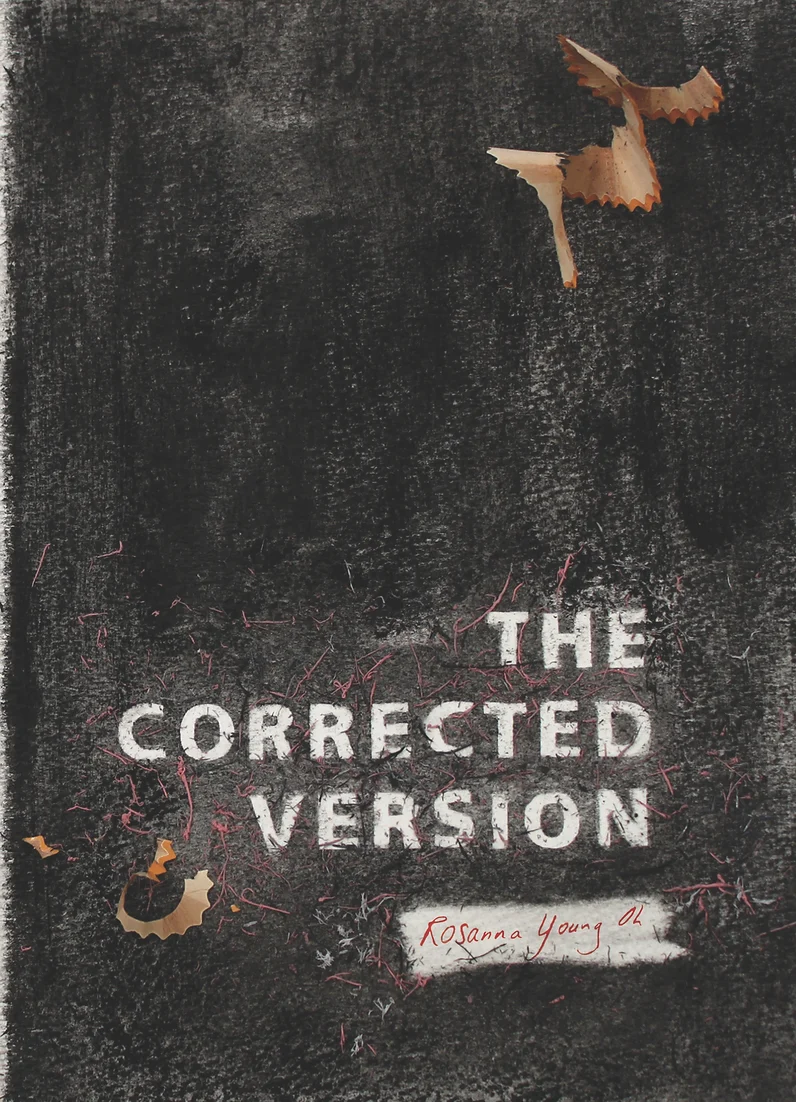

In The Corrected Version, Rosanna Young Oh Honors and Uplifts the Interior World

In a poem titled “The Yellow Bathing Suit,” which falls near the end of The Corrected Version, Rosanna Young Oh’s debut poetry collection, the speaker marvels at “yellow warblers in the window / …supreme and unperturbed.” In the next stanza, Oh watches an unspecified and intimate “you” fry eggs on the stove, close to this majestic scene yet unaware of it as they stand in the kitchen “wearing a floor-length bathrobe, / one shoulder baring a mustard-colored bra strap.”

This striking, specific image illuminates a broader theme of the book, which won the Diode Editions Book Contest and hit shelves this spring. Throughout its pages, Oh frequently juxtaposes the expansive worlds of myth and nature—from the jewel-toned depths of a koi pond, to the soaring heights of snow-capped Mount Fuji—with the cramped, lived-in spaces of everyday life. Just as “The Yellow Bathing Suit” places the reader in an apartment kitchen, other poems in the book invite the reader behind a grocery store register, into aisles teeming with lettuce and squash, and into an office where a landline phone and meat cleavers hang on the wall.

These settings are reminiscent of the speaker’s childhood, defined largely by the grocery store her family owns and where she spends most of her days. Though literally contained, this space is metaphorically sprawling and infinite—for Oh, it’s a world in itself, one in which she observes family, heritage, love, and ambition, as well as regret, mortality, and xenophobia. In line with these prevailing, oppositional threads of darkness and light, the collection’s speaker holds a deep reverence for home, alongside a pull to escape it.

The poem “The Gift,” which begins with a customer calling a bruised mango garbage and telling the speaker’s father to give it to his children instead, most vividly illustrates these dualities at the heart of the book: “But even I knew as a child / mangoes were the sweetest / when they looked half-rotten—/ I wanted to eat what the customer said was mine.”

Fruit becomes a metaphor for how people are both victimized by violence and enact it themselves. The rejection of the mango—“brindled with black and bruises”—mirrors society’s rejection of Oh’s immigrant and working-class family. Yet it also appears as a symbol in the interactions between the family itself: “My parents fought later. / My father punched a hole into a cantaloupe / instead of my mother.” Stanzas later, there’s a subtle suggestion that this violence will ripple through generations, as Oh recalls, “My two brothers impaled moldy oranges / on Ticonderoga pencils.” In another poem, “Picking Blueberries,” the speaker’s father “squeezes a blueberry / between his thumb and finger until the skin tears.”

As these images suggest, the fruit in The Corrected Version, at times painted so lush and ripe as to be almost tasteable to the reader, is also perilous and frail. Fruit goes bad. The speaker recounts visiting her sick grandfather in the hospital and finding him “eating from a plastic tray: / a single apple … orange juice from concentrate.” This counters earlier depictions of fruit as natural and life-giving, instead associating it with a sterile, lonely environment and with mortality. In another poem, the speaker’s father must battle with a refrigerator—a battle endowed with stakes like the family’s business and livelihood. This perilousness, sometimes deliberately emphasized and always just below the surface, is a nod to the lives and identities of immigrants.

The store and the lives of the family members within it are at the heart of The Corrected Version. Yet the collection also makes it easy to imagine if their lives had ended up completely differently. Early on in the book, the father tells his daughter she was “not meant to live this kind of life.” She remarks, “But nor was he—/ a man with a mind made wide by books, / who as a child rose with the sun to read by its light.” Though others call her father “the melon man,” seeing his life as a series of daily physical tasks, here Oh exalts his interior life, honoring his scholarly, ambitious mind. Oh also expresses the same wistfulness toward her mother, writing, “We were both filled with wishes,/ my mother and I, / she let hers burn / and I went to read mine in a book of poems.” In these lines, it’s clear why The Corrected Version was selected as the collection’s title. Oh rewrites common narratives to tell her family’s stories and her own, establishing her writing life as not only a trajectory, but a prophecy.

Order The Corrected Version here.