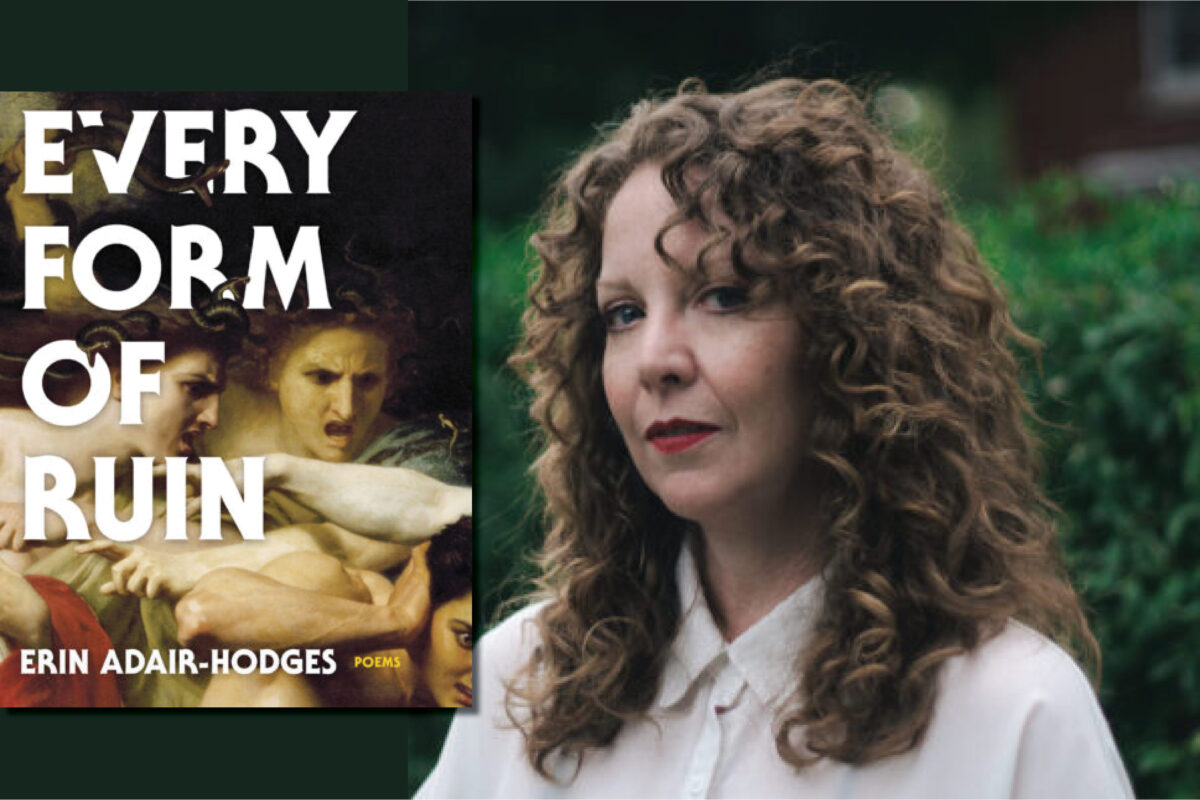

In Erin Adair-Hodges’s Every Form of Ruin, Women Are Both Dangerous and Endangered

“The dogwood was threatening / to swallow back the garden’s light, / so I borrowed a chainsaw and gas.” So reads the first three lines in “Black Thumb,” the opening poem in Erin Adair-Hodges’s sophomore collection, Every Form of Ruin. Through this first crucial image and action, the poem immediately places the speaker within a tense, ever-present juxtaposition that will come to define the book.

The dogwood and the garden evoke an idyllic home – one that’s in harmony with the natural world around it, almost a refuge or sanctuary. This image likely stirs up just as much envy as it does admiration. But it’s quickly contrasted with the mention of “a chainsaw and gas,” as well as the aptly chosen verb “threatening,” which sits poised and hovering at the end of the first line, prompting the reader to pause in a moment of fear and uncertainty. Even the poem’s title, “Black Thumb,” takes a typical adage – the idea of a “green thumb” – and urges us to examine it differently. The playful, self-deprecating language sharpens to incriminate a killer, one whose son “eyes [her] / holding the humming saw” from his bedroom window. This unexpected distance between mother and son echoes the othering of a woman from her tranquil and domestic surroundings.

Adair-Hodges creates this physical feeling of discomfort again and again throughout Every Form of Ruin, often in the very places where one expects to feel comfortable. In one poem, which depicts a walk with friends, the speaker falls. This seemingly unextraordinary moment becomes a metaphor for and a meditation on body image, the experience of aging in a female body, violence against women perpetrated by both men and the physical world, and even mortality itself. “I was dying a little all the time, and it made me mad, / I mean I was mad with it,” Adair-Hodges remarks.

She begins the poem “I Have Cried Off All My Makeup” with just as small and innocent of a moment, chronicling a woman working in an office looking for a stapler. This stapler stands in for the idea of security, however, something the poem’s speaker is desperately trying to grab onto. “Men have trouble guessing my age / which makes it hard for them to know / in which way to dismiss me,” she writes. “…I don’t know where I am / and wind to the river, ask its banks / what it is they are hungry for. Is it me?” These lines, beginning in an office and ending standing at the edge of a current, reveal a trademark of Adair-Hodges’s poetry: Her windows into a poem are often narrow and anecdotal, before widening to encompass the most open, wild settings and most universal questions. There are also distinctly gendered elements to these questions, as a woman aging pivots immediately to instability and the idea of death, or the “swallowing” alluded to in Every Form of Ruin’s opening poem. Broadening the poems in this way feels visceral, decisive, and highly physical. One could imagine Adair-Hodges tearing a curtain or clearing an overgrown brush with the aforementioned chainsaw, letting us in on an eerie and hidden world we question if we are supposed to see. Later, in “Panic Attack at Applebee’s,” she confronts the “adrenaline vision” of being surrounded by huge television screens and describes the many types of fries on the menu as “potato’s infinite faces.”

Within these scenes – some natural and timeless, others distinctly modern and manmade – Adair-Hodges prods at the odd details and small events of daily life until they become nightmarish. As a reader, it becomes easy to imagine two parallel scenarios: One where a visit to a chain restaurant is just as bland as we’d expect, an experience to endure on autopilot, and another where the stakes underlying it are on the scale of life and death. As the poet catapults us between these two moods and mindsets, often in the course of just a few lines, it’s hard to pinpoint which reality is scarier: That life is a constant foray into danger, or that it is truly safe, sheltered, and predictable.

Within both of these realities, Adair-Hodges isn’t afraid to cast herself as a villain. In the surrealist Applebee’s landscape, she makes herself godlike and mythological: “Now here I am, pulled full-grown / from the margarita machine–I’m slush-blooded, / sweet enough to rot.” This image teems with an otherworldliness and dark hilarity that poems like “Mostly Married, Alone at Night” reject. “When have my lips ever done what they should? For all I know / they’re out there now, surveying skin, working their way / across some tattooed frontier and, since they’re white / claiming and renaming what they find,” this poem asserts. Here, the speaker’s very humanity and security is the danger she presents, as the “safe” and “neutral” ideal of white womanhood weaponizes itself and threatens to encroach on everything. The trope of the bored housewife evoked by the title delves into twisted and all-powerful wish fulfillment. Is it evil to claim what we want? Once we have it, will we still want it?

These big-picture questions ask about the interior world, an ambiguous idea that the poet strives to embody and render tangible throughout Every Form of Ruin. As the speaker feels increasingly uncomfortable, isolated, and afraid in her surroundings, she writes, “Since it is a house made entirely from / the past and future I can’t stay there.” In this line, she sums up the exacting truth that women have only ever been capable of living in one place: the body and its simmering, activating anger.

Order Every Form of Ruin here.