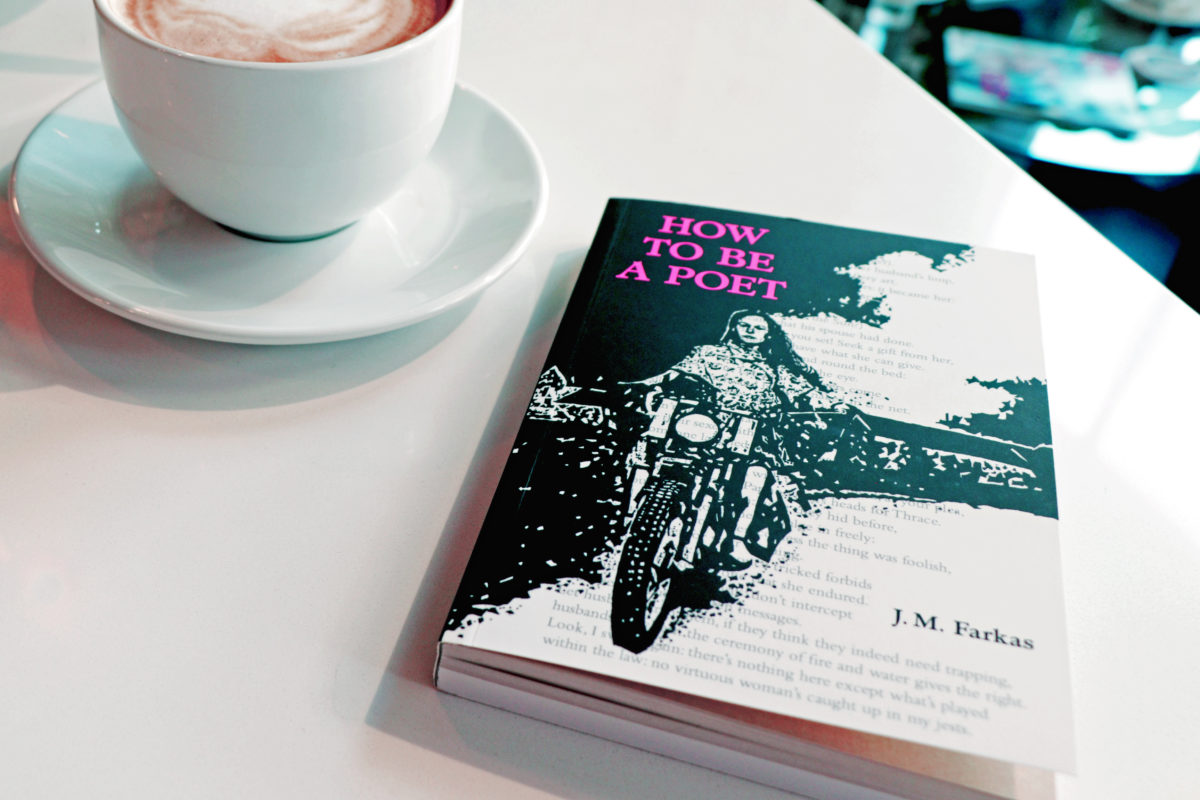

J.M. Farkas Talks Girlhood, Recklessness, and Process

“Poetry is all about emotion, drama, curiosity, gossip, cruelty, discovery, tenderness, heartbreak. All of these things seem inherent and heightened in girlhood.”

Author of Be Brave and the forthcoming How to Be A Poet, J.M. Farkas has the unique ability to turn old into new. Both collections of poetry are done in the blackout style, meaning that the source text is covered or “blacked-out” to leave behind only a few words that make the poem. With How to Be a Poet on the horizon, J.M. Farkas took a moment for a quick Q&A, sharing with us some of her favorite work, her inspirations, and reflections on her life as a poet.

Thea Voutiritsas: What are you currently reading?

J.M. Farkas: I currently have a stack of about 10 books out from the library, in addition to my incurable book-buying habit. Right now, I’m reading Ann Patchett, Emmalea Russo, Jia Tolentino, Emily Vizzo, Dani Shapiro, and Hans Christian Andersen. I’m excited about Nina MachLaughlin’s retelling of the myths in Metamorphosis, called: Wake, Siren: Ovid Resung.

TV: Who are your favorite poets and how did you discover them?

JMF: Some of my favorite old-school poets are Neruda and Edna St. Vincent Millay. Some of my favorite contemporary poets are Louise Glück, Traci Brimhall, Jane Hirshfield, and Ada Limón. When I first discovered poetry, I was big on reading anthologies, like Best American Poets, and then I would go deeper and buy full collections of poets I admired. I also love and highly recommend the websites Verse Daily and the Poetry Foundation’s Poem of the Day. I also keep up with literary magazines to discover new writers.

TV: How did you discover Ars Amatoria and what made you want to use it as source text?

JMF: I first read it in graduate school with my advisor, the wonderful poet, Richard Jackson. It was rumored that Ovid, who is most known for writing the Metamorphosis, was exiled because of the scandalous nature of Ars Amatoria, which is essentially an ancient poetic manual on dating, relationships, and sex. Immediately, I was intrigued, but when I started reading it, I was so stunned by how modern and funny and offensive Ovid could be. At times, it reminded me of those ridiculous dating books from way back, like, The Rules.

TV: How did you find the process of blacking out Beowulf for Be Brave different from Ars Amatoria for How to Be a Poet?

JMF: Be Brave came out of a pure need to get myself through a difficult situation and work through a period of writer’s block. I didn’t envision it as a book or something that I would necessarily share with other people. With How to Be a Poet, I was very aware that this was my second book, so there was more self-consciousness and deliberateness. That being said, once I got into the groove of the erasure process, it felt very much the same, in the sense of the obsessive way I comb through a source text, looking to create an alternative and transformative narrative.

TV: How to Be a Poet is a message to poets but also to young girls. In what ways do you see poetry as a metaphor for girlhood?

JMF: Poetry is all about emotion, drama, curiosity, gossip, cruelty, discovery, tenderness, heartbreak. All of these things seem inherent and heightened in girlhood. I tend to write my poems about this stage of growing up too.

TV: Did you have a theme in mind before you began, or did the meaning emerge as you worked?

JMF: I didn’t have a theme. Especially with erasure poetry, the work tends to reveal itself as you progress through the pages. It usually starts with much unknowing, where I’m simply gathering or considering words or phrases I love; but there is this moment when something clicks, and I realize I have a real “thing” that is coming into focus and building upon itself with a loose narrative. With How to Be a Poet, for example, I don’t think I realized that I was speaking to girls, until several pages in, when I landed upon the line: “Be the girl who is too beautiful.” Then I knew I wanted the entire book to continue in this same way, speaking to this same female reader.

“Erasure is all about faith–the idea that what you are looking for is already there.”

TV: Tell us about your process. How do you take a page full of words down to a new meaning?

JMF: It’s a very mysterious process that I wrote about a bit in the introduction to my first book, Be Brave. Usually, I read the source text or have read it in the past, but I don’t read the book while I’m erasing. Rather, certain words seem to lift off the page and call to me, and then I try to connect them to the next word or phrase on the following page. There are many times when I’m searching for a specific word to create a very specific line, and often, that exact word that I need will appear. Erasure is all about faith–the idea that what you are looking for is already there.

TV: You quote Shirley Dent in saying “There is precise science in the recklessness of both riding a bike and writing a poem.” Can you explain what that means?

JMF: Like any good metaphor, I love the connection between unlikely things, such as poetry and motorcycles. I was very drawn to the inherent contradiction in both endeavors—this need for both precision and recklessness, stillness and motion. I also enjoy the almost-homophone with the words writing and riding.

TV: How do you stay inspired and keep things fresh?

JMF: Reading is the best way to stay inspired, but hearing from my readers has also propelled me forward in a new way. Movies and films have always had a way of loosening my creative-juices. I’m a big believer in going to the movies solo and sitting by yourself in the dark. I think that heightens the emotional and imagistic experience.

TV: Do you feel like poems should have to be solved, or should they be straightforward for the reader?

JMF: When I was in high school, I used to think poetry is something beautiful that I can’t understand. So, I think it can be very important for people who are new to poetry to realize that poems can be remarkably accessible and understandable. Poetry is like music, there are so many styles, and it’s just a matter of finding the kind you like and what moves you. As a reader continues to immerse herself in more poetry, I think tolerance and even, excitement, grow for more challenging or “difficult” poems. Overall, a poem should never “have to be” anything.

Photo source: @jmfarkas on Instagram

TV: Did teaching change your relationship to writing, or poetry at all? And if so, how?

JMF: Absolutely. I love introducing students—or anyone really—to poetry. I like prescribing it to a specific person or someone going through a specific situation, or just somebody desiring a certain emotional experience. I was also incredibly invested in my own students’ writing. Many of their pieces were born from models of contemporary writers, which resulted in incredible work. My students blew my mind with their raw writing talent and willingness to open up and be vulnerable on the page. They often inspired me to do the same.

TV: Did publishing your first book change your process for writing? If so, how?

JMF: In terms of erasure, it did, in an unexpected way. I realized that I needed to get the copyrights or permissions for translations before I started the blackout process. With ancient texts like Beowulf or Ovid, most people assume that the work is in the public domain because it’s so old; however, the translations can be contemporary and are often copyrighted. For Be Brave, I had to hunt down the estate and literary agent of the famous translator Burton Raffel who passed away well after I finished the project. If I didn’t get permission, it was possible that my book would not be published. Thankfully his family granted me the rights, but now I make sure I have the rights first before I begin a new project.

TV: Do you read your reviews?

JMF: Absolutely. I don’t know how anyone can resist this temptation. One of the reasons I write is to connect with readers, and so when that happens through a review or shared anecdote, I’m truly elated. For example, one of my favorite bookstagram accounts Folded Pages Distillery shared Be Brave with a 13-year-old girl who was upset about moving to a new state. Something in my book touched her during the exact time when she most needed it. Hearing this kind of thing is the best possible “review.”

Of course, the flip side is understanding that you will not connect with every reader. What helps me deal with bad reviews is looking up Amazon reviews of some of my favorite books. An entire five disastrously-wrong people have given Jonathan Safran Foer’s Everything Is Illuminated one star! This makes me realize that everyone has different tastes, and there is no way to please everybody.

“I bring a lot of fears to the table when I first begin or am staring at a blank page or screen. Once I get into the flow, I’m golden, but it can be difficult for me to get to that place.”

TV: What’s the biggest mistake you’ve made as a writer?

JMF: In general, I struggle quite a bit with writing and tend to get in my way. I bring a lot of fears to the table when I first begin or am staring at a blank page or screen. Once I get into the flow, I’m golden, but it can be difficult for me to get to that place. My biggest mistake, I think, has been hoping that these fears will go away or letting them stop me from moving forward—instead of accepting that this painful “stuff” is all part of the process and believing that I can move through the hard parts because history has shown that I can.

TV: What does literary success look like to you?

JMF: I have a somewhat troubled relationship with both of the words “literary” and “success.” I hope to continue to create new work in several genres of writing. To get better with each project (I love the word: project!)—and most importantly, to try to find and hold onto as much joy and faith in the writing process.

TV: Have your feelings towards your past work changed over time?

JMF: I look at past work almost like a time capsule or diary even. Whether or not the work is “true,” it does provide a certain kind of evidence for who you were at that time—for better or for worse. In general, I try to view my younger self, and my younger writing-self, with as much generosity and kindness (and sometimes, forgiveness) as possible.